Pt 1. Intro. Don't gobblefunk around with words

Long-form musings on language, communication disability and discrimination

INTRODUCTION

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.’

’The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

’The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master — that’s all.’- Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

Have you been told that using preferred pronouns is a courtesy?

Have you been told that using words such as ‘cis’ adds clarity?

Have you been told that using phrases such as ‘pregnant people’ is inclusive?

None of it is true.

NONE OF IT IS TRUE.

I explain here why it’s neither simple, nor a courtesy nor inclusive.

What is it? It’s INCORRECT. It’s CONFUSING. It’s DISCRIMINATORY.

You might find the following deep dive into language, its disorders and discrimination useful. It is relevant in every area of life. People with communication disabilities are in every area of life. They are you and me, our children, our parents, all our relatives, our colleagues, our friends, our peers, our neighbours. Use this in schools, colleges, universities, hospitals, councils, businesses, courts, anywhere and everywhere.

Spread the word.

Here’s what you’re about to read:

I explain language and its use (and pronouns and ‘they’ in detail) and what makes up how we usually communicate. If you’re already expert in all of that stuff, I ask you to read it anyway and if you spot any inadvertent errors, do let me know.

I describe communication disabilities in children

I then look at adults with communication disabilities

I share information on how it is discriminatory to impose language demands.

I share my opinion throughout and the difference between objectivity and subjectivity should be clear to the careful reader.

There are lots of references and links to other resources. Please use what you find relevant to your situation. You can read it all or skip to the bits that you specifically need.

All links and references are included to help you understand or help you help others understand and take appropriate actions. You can use this information to hone your debating or persuasion skills and bring about change where it’s needed. I am not responsible for the content of those links and references and I have no idea what every author’s or participant’s stance on gender ideology is.

Where I have made errors of fact, I’m happy to correct them. Where you disagree with me, I’m open to changing my mind when the facts change.

PART ONE

What do we use to communicate?

I’m laying the groundwork here. Before we can better understand what communication disability entails and what discrimination looks like in that context, we need to understand how we usually communicate and what elements make that up.

Language is a rule-governed behaviour. It involves listening, speaking, reading, writing and signing. It has five domains:

- Semantics (vocabulary)

- Phonology (sounds)

- Syntax (sentence structure)

- Morphology (smallest meaningful part of a word)

- Pragmatics including discourse (social use of language, understanding points of view including in conversations)

Speech is formed by moving the articulatory muscles to create the shapes needed to form the sounds that make up the words.

Cognition is all the mental processes that lead to thoughts, knowledge, and awareness.

We also use our senses when we communicate such as sight, hearing and touch.

And some people speak more than one language.

Whilst voice or phonation forms part of communication, I’ve chosen not to cover it in detail in this summary. Suffice it to say, if you have a voice disorder, what you say may not be readily heard, which can lead to confusion and misunderstanding.

Now, let’s get into some nitty-gritty.

What’s a pronoun?

Pronouns replace nouns in a sentence. We have different ‘persons’ pronouns in the singular and plural so we know who we’re talking about and how many. Pronouns exist in different ‘cases’.

We learn them between 31 and 40 months old.

He has a coat. Is the coat his? Yes, it is his coat.

She has a pen. Is the pen hers? Yes, it is her pen.

We learn reflexive pronouns around 47 months old1.

He chose the coat himself.

She bought the pen herself.

Furthermore, in English, we do not have linguistic genders for inanimate (non-living) nouns, e.g. table, moon, or cup. Nor do we have linguistic genders for animate (living) nouns such as nurse, plumber, or writer, which could be either sex.

So we DO make changes to the pronouns we use based on the SEX of the living person we are talking about. The person we are talking about is an ‘animate referent’. We also do this for some lexical items such as girl-boy, sister-brother, mother-father, all of which correspond to she-he, her-him, hers-his, herself-himself. If a noun differentiates whether the living referent is male or female, we can also do this, e.g. actress-actor, princess-prince, waitress-waiter.

So pronouns for living things (people) are SEXED in English.

Jane has a pen. Does she have a pen? Yes, she has a pen. She bought it herself. It is hers. It belongs to her.

John has a coat. Does he have a coat? Yes, he has a coat. He chose it himself. It is his. It belongs to him.

When we look at a person, the vast majority of the time, from infancy on, we recognise the person’s biological sex2 and we use the corresponding pronoun.

The ‘singular they’ rabbit hole.

*‘They’ is grammatically plural. If it were grammatically singular, you would be saying “they is”. You’re not. And no-one ever has (outside of a few instances of dialect).

This use of ‘they’ is as a social implicature. It forms part of Grice’s Maxims and the flouting or violating of them, which are common and even useful. It is an example of the social-pragmatic use of language. One of many examples and reasons for this is because you do not know the sex of the individual concerned (or you want to hide it).

“Who was that at the door?” -> “I don’t know but they posted a leaflet through the letterbox.”

“Who broke the window?” -> “I don’t know I didn’t see them.”

“Someone left their bag on the coach.”

The use of ‘they’ when you do not know the sex of the individual is similar to asking, “who is it?” pragmatically. We don’t refer to humans as neuter ‘it’ unless we’re missing some information. You’re not imagining a bollard or a tractor, you’re imagining a person when someone asks, “Who is it?” The ‘it’ doesn’t suddenly contradict the ‘who’ and make you think of a thing rather than a person. You’re in 3rd person singular ‘he’ or ‘she’ territory, not actually ‘it’.

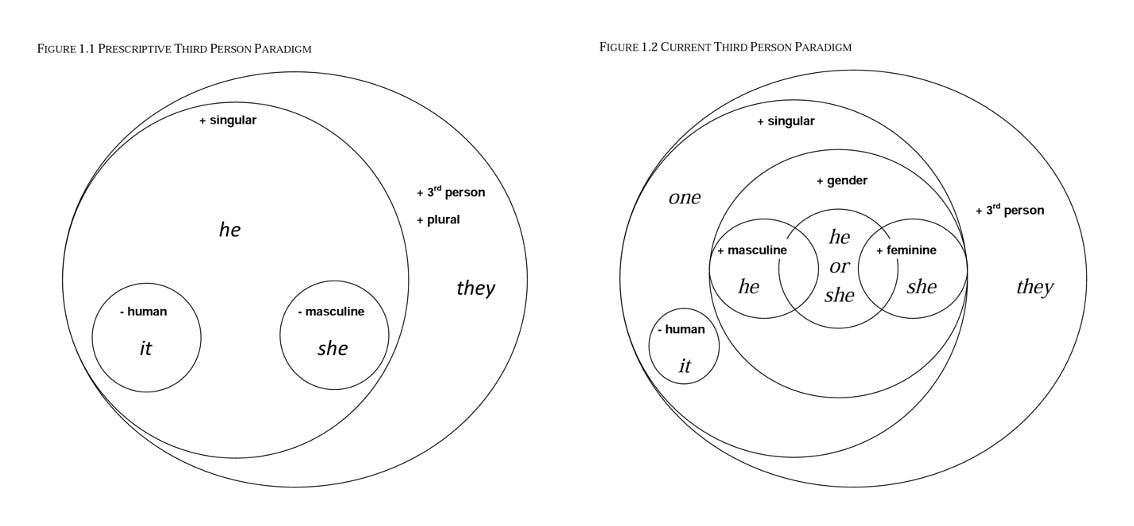

Some people claim that ‘they’ is an epicene3. But I assert that there is no grammatical third person singular epicene pronoun in English. You have ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘it’. That’s it.

‘He’ failed as an epicene, perhaps in part to feminism and ‘he or she’ is clumsy at times and ‘one’ works in formal, written language, but less so in informal written language and the spoken word. But perhaps I’m being a grammar prescriptivist. (Now go back and spot all my grammar errors and tell me about them).

Whilst I loathe the term “singular they” or “epicene they”, we (‘one’?) must agree that “they” has been used to refer to an individual for quite some time. It’s gone something like this:

The animate referent’s sex is unknown: use ‘they’ ->

The animate referent’s sex is known and the listener is already aware: use ‘they’ +/- ‘he’ or ‘she’

The animate referent’s sex is overridden by the social construct of ‘gender’ and asserts that ‘they’ must be the default until we know the individual’s preferred pronoun

Let’s leave ‘degendering’ for another blog.

For people without communication disability, 1. can be understood and used relatively easily (as evidenced by its widespread use), whereas 2. is more difficult as there is mixed use of ‘they’ with ‘he’ or ‘she’ in a sentence or paragraph, and 3. poses even greater problems as it creates confusion rather than ensuring clarity.

This brings me onto how I understand ‘they’, so that we can then understand why we need to be wary of its misapplication now and in future.

“Singular they” or “epicene they” are terms best understood as social-pragmatic. As such, ‘they’ does not follow the regular rules of English grammar, hence prescriptivist types get a bit annoyed. As I said earlier, we say “they are” and not “they is”. I don’t agree with listing ‘they’ in pronoun tables as anything other than plural because the tables are grammar tables not social-pragmatic use of English tables. Nor can we state ‘epicene’ in pronoun tables because English has never successfully had a 3rd person singular epicene pronoun.

It's entirely possible that you don’t have a communication disability but it’s already difficult enough to get one’s ahead around the linguistic complexities of it all. Imagine if you do have a communication disability. To what extent should you be expected to engage in changing your language?

PART TWO out soon. Keep an eye on your inbox.

Vollmer, E., 2020. Pronoun Acquisition | Child Development | TherapyWorks https://therapyworks.com/blog/language-development/speech-strategies/pronoun-acquisition/

Kayl, A. J. 2012. Do Toddlers Exhibit Same-Sex Preferences for Adult Facial Stimuli? UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1676. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/4332657

Paterson, L. L. 2011. The use and prescription of epicene pronouns: a corpus-based approach to generic he and singular they in British English. Loughborough University. Thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/9118