PART TWO

Communication Disability

From time to time, we all find it difficult to communicate. We’ve all experienced the ‘tip of the tongue phenomenon’1 - “What is that actor’s name? You know, thingy, he was in that film with all those things happening…” or slurred speech from tiredness, illness, medication or inebriation, or quiet, breathy voice because of nervousness or anxiety.

There are some children and adults who experience a more pervasive communication difficulty. It is either developmental or acquired, it may be consistent or variable, it may be temporary or permanent.

These are children and adults who cannot process the English language effectively or consistently such that they cannot understand and/or or use pronouns (before any other demands are made on them to change pronoun usage), or neologisms (new, made-up words) like “cisgender” or confusing or unclear language such as gender-neutral language like “person with a cervix” or “menstruators”.

Here in PART TWO, I talk about communication disability in children. In PART THREE, communication disability in adults. And then the legal bit on discrimination in PART FOUR.

Don't gobblefunk around with words.

- Roald Dahl, The BFG

CHILDREN

The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists provides the following list of difficulties in children, for whom speech and language therapists provide treatment:

Dyslexia

Language delay

Learning difficulties – mild, moderate or severe

Physical disabilities

Specific difficulties in producing sounds

Stammering

Some children have more than one of these communication disabilities at the same time. It is not unusual for children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) who may also have support from a Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO) to be eligible for an Education, Health and Care (EHC) Plan.

As outlined by the Government:

Special educational needs and disabilities (SEND)

All publicly funded pre-schools, nurseries, state schools and local authorities must try to identify and help assess children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND).

If a child has an education, health and care (EHC) plan or a statement of special educational needs, these must be reviewed annually. From Year 9 the child will get a full review to understand what support they will need to prepare them for adulthood.

Higher education

All universities and higher education colleges should have a person in charge of disability issues that you can talk to about the support they offer.

You can also ask local social services for an assessment to help with your day-to-day living needs.

Let’s look at some examples where children find it difficult to communicate in relation to pronouns and in a wider language context.

ADHD/Autism/Neurodevelopmental disability

If your child has Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or one of many other neurodevelopmental or unknown cause disorders, it may be more difficult to self-monitor his or her language and adapt it accordingly. There are also sex differences2,3 in prevalence and presentation of ADHD and ASD in boys and girls. These diagnoses are more difficult to spot in girls and leads to underdiagnosis.

In addition, a child may experience deficits in theory of mind, perspective-taking and inhibition, all of which result in pronoun errors in everyday speech.4, 5, 6 A child cannot always help what words he or she says.

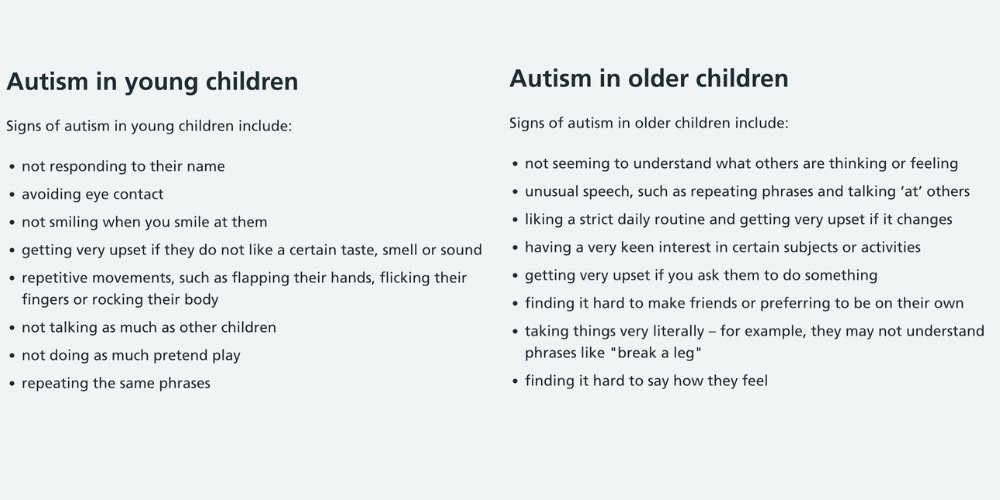

So many of the signs of ADHD and Autism listed on the NHS' own website are directly related to communication and social interaction skills and yet the use of confusing language is promoted in healthcare and education, where these vulnerable children and young people need the most support.

Here's a lovely animation about ADHD:

And here’s a great playlist on Autism.

Developmental Language Delay (DLD) and Aphasia

Some children experience cognitive or language delay or disorder, developmental or acquired, such as Developmental Language Disorder - DLD7 (previously Specific Language Impairment - SLI) or Childhood Aphasia8.

The signs of DLD are that:

Children may not talk as much and find it difficult to express themselves verbally.

His language may sound immature for his age.

She may struggle to find words or to use varied vocabulary.

Children may not understand, or remember, what has been said.

Older children may have difficulties reading and using written language

Aphasia is another language disorder. Children with Aphasia have similar symptoms to adults with Aphasia though the child is still learning language.

Anomia: difficulty finding the correct word

Use of empty or filler words: such as “thing,” “stuff,” “you know,” and “uh”/“um”

Incorrect grammatical constructions

Paraphasias: word substitutions such as “chair” for “stool”; phonemic substitutions such as “spool” for “stool”; nonword substitutions (i.e., neologisms) such as “flimly” for “stool”

Jargon: strings of unintelligible speech generally made up of multiple neologisms

Poor language comprehension–Inability to follow commands–Difficulty grasping the point of a conversation

Verbal perseveration

Word deafness: an inability to comprehend the meaning of words despite intact hearing abilities

As a result, the child may not be capable of neurologically processing the understanding or expression of pronouns consistent with the referent’s sex even if the child knows whether the person is a man or woman.

Or, he may accidentally use the wrong noun (‘man’ for ‘woman’ and vice versa) and thus whilst the pronoun matches the noun sex, it is incorrect in reality.

The child may not be able to learn new words readily and consistently.

Here's a short animation by a teenage girl who was diagnosed with DLD late and explains how it affects her and makes her feel:

For the characteristics of childhood aphasia, check this out:

Articulation disorders

There are children with articulation and fluency disorders,9 such as stammering, cluttering10, tongue-tie, cleft-palate, phonological disorders, apraxia of speech or dysarthria amongst others.

Signs and symptoms of functional speech sound disorders include the following:

omissions/deletions—certain sounds are omitted or deleted (e.g., "cu" for "cup" and "poon" for "spoon")

substitutions—one or more sounds are substituted, which may result in loss of phonemic contrast (e.g., "thing" for "sing" and "wabbit" for "rabbit")

additions—one or more extra sounds are added or inserted into a word (e.g., "buhlack" for "black")

distortions—sounds are altered or changed (e.g., a lateral "s")

syllable-level errors—weak syllables are deleted (e.g., "tephone" for "telephone")

Stammering, or stuttering, is when a child:

stretches sounds in a word ("I want a ssstory.")

repeats parts of words several times ("mu-mu-mu-mu-mummy.")

gets stuck on the first sound of a word so no sound comes out for a few seconds ("...I got a teddy.")

puts extra effort into saying specific sounds or words. You might notice tension in the face eg around the eyes, lips and jaw

holds their breath or take a big breath before speaking, so their breathing seems uneven

uses other body movements to help get a word out - they might stamp their foot or move their head

loses eye-contact when getting stuck on a word

starts to try to hide their stammer: they might pretend they’ve forgotten what they want to say, change a word they have started to say or go unusually quiet.

Whilst the child may be trying to articulate the word the listener expects, it may not be fully intelligible to the listener and (repeatedly) misunderstood. It would also be very challenging for a child to articulate neopronouns or other neologisms consistently.

Listen to these children who stammer and see if you think asking further demands of their speech is fair or reasonable:

Selective mutism

A child with selective mutism11 is already experiencing a speech phobia and fears disapproval, significantly limiting his or her speech or even remaining completely silent.

A child may avoid eye contact and appear:

nervous, uneasy or socially awkward

rude, disinterested or sulky

clingy

shy and withdrawn

stiff, tense or poorly co-ordinated

stubborn or aggressive, having temper tantrums when they get home from school, or getting angry when questioned by parents

Imagine demanding of her to use preferred pronouns. Or that she had begun to speak following intensive therapy but is then corrected for using the ‘wrong’ pronoun and returns to mute.

This documentary covers selective mutism as well as other conditions that prove challenging for children, their families and schools:

Hearing impairment and d/Deafness*

If your child is d/Deaf or has a hearing impairment and does not hear a word effectively, she may misunderstand its meaning and/or cannot articulate that word clearly, especially if it is a neologism and even more so if it does not follow the phonotactic rules of English.

d/Deaf children may also experience pragmatic difficulties.

Obvious difficulties include not:

using appropriate eye contact

starting, joining in and maintaining conversations

joining in during structured activities with peers

saying appropriate, related things during conversations

sharing

varying their language use

More subtle difficulties include not:

using their imaginations or participating in imaginative play

creating and retelling stories and personal narratives in an organised way

understanding their emotions and feelings and those of the people around them

trying to take on someone else's view point and imagining how they think and feel

understanding when someone doesn’t really mean what they say, for example, when someone is being sarcastic or where there’s a hidden meaning.

And as the NDCS further points out:

Even when a child has an age-appropriate knowledge of words and their meaning, they might not have learned how to use this knowledge in a socially appropriate manner. This can make it harder for deaf children to make friends, so it’s important to encourage them to develop their pragmatics so they can form good relationships with family and friends.

d/Deaf and hearing-impaired children can thrive in the right communication environment. They don’t need extra demands on them or barriers placed in their way.

Here are some great tips for children with hearing impairment in special schools:

And this is what it’s like to be a child with mild hearing loss in the mainstream classroom and what teachers can do:

And here is the deaf-blind manual explained in a video:

Auditory Processing Disorder

I um’d and ah’d whether to include this as it’s a much debated diagnosis. Given that there are children out there in the UK with the diagnosis, I’ve included it.

A child diagnosed with Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) can hear but his brain cannot interpret the speech sounds.

Signs of APD include difficulties understanding:

people speaking in noisy places

people with strong accents or fast talkers

similar sounding words

spoken instructions

There remains much more research to do be done on APD.12 Nonetheless, if a child is showing these signs, then don't expect them to follow confusing or complex language or odd new words consistently.

Here’s Professor Dorothy Bishop talking about understanding APD and why it’s controversial:

Summary

It is already a challenge for those without communication disabilities to remember and articulate neologisms/neopronouns such as:

Xe/xem/xyrs/xemself

Xy/xyr/xyrs/xyrself

Hi/hir/hirs/hirself

Ze/zir/zirs/zirself

Ey/em/eirs/emself

Ne/nem/nems/nemself

Fae/faer/faers/faerself

Ae/aer/aers/aerself

Thon/thon/thon/thonself

Per/per/pers/perself

Ve/ver/vers/verself

Zee/zed/zeta/zetas/zedself

Now imagine having a cognitive, learning, sensory, speech or language disability and being expected to understand or use these.

Every single one of these conditions means that children can make errors in understanding or using grammatically and pragmatically regular pronouns. To then ask them to process ‘preferred’ pronouns or neopronouns (neologisms) or other confusing terms is asking them to do something they are unable to do effectively, consistently or at all.

It is a demand on their system that they cannot reasonably meet. This will manifest differently dependent on the condition, the child and the communication circumstances.

And of course, there are children out there who no-one has spotted has a communication disability, has been unfortunately mis-diagnosed, or is not receiving the therapy and support they need.

In PART THREE, we look at adults with communication disability. Keep an eye on your inbox again.

*d/Deaf For an explanation of little d and big D, see here.

Kim J, Kim M, Yoon JH. 2020. The tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon in older adults with subjective memory complaints. PLoS One. Sep 18;15(9):e0239327. https://doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0239327

Lundström, S., Mårland, C., Kuja-Halkola, R., Anckarsäter, H., Lichtenstein, P., Gillberg, C., Nilsson, T. 2019. Assessing autism in females: The importance of a sex-specific comparison. Psychiatry Research,Volume 282, 112566, ISSN 0165-1781, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112566

Quinn, P.O., Madhoo, M. 2014. A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in women and girls: uncovering this hidden diagnosis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 16(3):PCC.13r01596. doi: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.13r01596

Kuijper, S.J.M., Hartman, C.A., Hendriks, P. 2021. Children's Pronoun Interpretation Problems Are Related to Theory of Mind and Inhibition, But Not Working Memory. Front Psychol. Jun 4;12:610401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.610401

Perovic, A., Modyanova, N., Wexler, K., 2013. Comprehension of reflexive and personal pronouns in children with autism: A syntactic or pragmatic deficit?. Applied Psycholinguistics, 34(4), pp.813-835 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716412000033

Finnegan, E.G., Asaro-Saddler, K., Zajic, M.C. 2021. Production and comprehension of pronouns in individuals with autism: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Autism. Jan;25(1):3-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320949103

Snowling, M.J., Nash, H.M., Gooch, D.C., Hayiou‐Thomas, M.E., Hulme, C. and Wellcome Language and Reading Project Team, 2019. Developmental outcomes for children at high risk of dyslexia and children with developmental language disorder. Child development, 90(5), pp.e548-e564. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13216

Council, R.O. and Richman, S., 2022. Aphasia, Acquired Childhood. [Online] https://www.ebsco.com/sites/g/files/nabnos191/files/acquiadam-assets/Rehabilitation-Reference-Center-Clinical-Review-Aphasia-Acquired-Childhood.pdf Accessed 30/01/23.

Bommangoudar, J.S., Chandrashekhar, S., Shetty, S., Sidral, S. 2020. Pedodontist's Role in Managing Speech Impairments Due to Structural Imperfections and Oral Habits: A Literature Review. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. Jan-Feb;13(1):85-90. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1745

Alm, P.A. 2013. ‘Cluttering: a neurological perspective’. In: Ward, D and Scott, K.S. (Eds) Cluttering A Handbook of Research, Intervention and Education. East Sussex: Psychology Press, Pt1, 17-43.

Catchpole, R., Young, A., Baer, S., Salih, T. 2019. Examining a novel, parent child interaction therapy-informed, behavioral treatment of selective mutism. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. Volume 66, 102112, ISSN 0887-6185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.102112

Neijenhuis, K., Campbell, N,G., Cromb, M., Luinge, M.R., Moore, D.R., Rosen, S., de Wit, E. 2019. An Evidence-Based Perspective on "Misconceptions" Regarding Pediatric Auditory Processing Disorder. Front Neurol. Mar 26;10:287. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00287