PART THREE

A reporter once sent Cary Grant the telegram, “How old Cary Grant?” He replied, “Old Cary Grant fine.”

― Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language

In PART ONE we took a deep dive into some of the relevant language aspects.

In PART TWO we looked at communication disabilities in children.

Welcome to PART THREE.

And in PART FOUR, we’ll look at the legal bit on discrimination.

ADULTS

Adults experience communication disabilities such as:

Aphasia - difficulty understanding and/or using language/words

Apraxia of Speech - motor programming disorder affecting articulation

Dysarthria - weakness of muscles affecting articulation

Dysfluency - stammering/stuttering

Cognitive-Communication Disorder - difficulties in processing thoughts, knowledge, and awareness affecting communication

Sensory impairment - hearing, seeing and touch

Dysphonia - voice problems

These are often acquired though some are developmental, may be temporary or permanent, consistent or variable. Some of the underlying causes of communication disability include:

Stroke

Brain injury including tumours and its treatment

Progressive neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s Disease, Motor Neuron Disease, Multiple Sclerosis or Huntington’s Disease

Dementia

Head & Neck cancer and its treatment

Learning Disability

Autism

Mental Health conditions such as schizophrenia

How might adults with communication disabilities find it difficult to understand or use preferred pronouns or “gender-neutral” language? Let’s explore some of the communication disabilities adults experience.

Aphasia

Aphasia is sometimes known as ‘dysphasia’. It is a language disorder that occurs when the brain is damaged. In most people, language is processed in the left side of the brain. Damage to this can affect a person’s ability to understand, talk, read or write or sign. The severity may be mild to profound.

Understanding

A person with aphasia cannot understand other people’s words, especially if they are complex, or lengthy utterances or spoken fast. Those with profound or severe aphasia may not consistently understand simple, single words such as ‘cup’, ‘pen’ or ‘bed’. Those with mild to moderate aphasia may struggle with sentences like, “The carpet the cat is on is red” or “The dog is chased by the cat”.

“People with a cervix” is definitely much harder to understand than “women”.

It’s also more difficult to understand what people are saying in loud or busy environments even if the person can hear perfectly well.

It can also be tricky to understand jokes.

Talking

When it comes to expressing language, many people with aphasia experience word-finding difficulties. This is a bit like the tip of the tongue phenomenon we all experience from time to time but turned up to the max. Many people will say they know the word in their head but cannot say it out loud, “We had a really lovely time, we went to… er, you know, … that place, so yeah, it was nice.”

It is common for people to say the wrong word. Sometimes it shares a category or sometimes it sounds similar, and sometimes both. Or sometimes it’s completely unrelated.

For example:

Target word is “Dog”. A person with aphasia could say:

Cat

Og

Dat

D d d d d

Pet

Animal, four legs, barks

Fido

Bird

Cup

It was this, when I had it, so they went there and all…yes, it was, ah.

This means that a person with aphasia could also mix up any word including those that require knowledge of biological sex, so “man” for “woman” and vice versa, when in fact he knows what sex the individual is but accidentally says the wrong word from the same category (nouns for the sexes).

Sometimes parts of words and their sounds get switched around so instead of saying “postman” the person says, “mostpan”.

Some words are completely unintentionally made-up such as “workle”, “daffgo”, or “sweetch”.

It is usually easier to say single words or phrases that come easily rather than whole sentences. So she might be able to say, “tea”, “toilet”, “hairbrush” or count to ten or say the days of the week in order but cannot say, “There were two of us who went out to tea on Monday”.

And sometimes made-up words are used with real words in a sentence but it doesn’t make sense, “I went to the fingle for the datter and it was all libbered”.

People with hearing impairment who use sign language are also affected by aphasia.1 Sign language is language and understanding or expression can be impaired.

If it’s difficult to understand and/or express the spoken or signed word, then it is also difficult to read or write, use numbers, count/do maths or tell the time, either consistently or at all.

Agrammatism

There is also an aspect of aphasia called agrammatism. This means that the person with aphasia cannot understand or use certain aspects of grammar effectively, including pronouns.

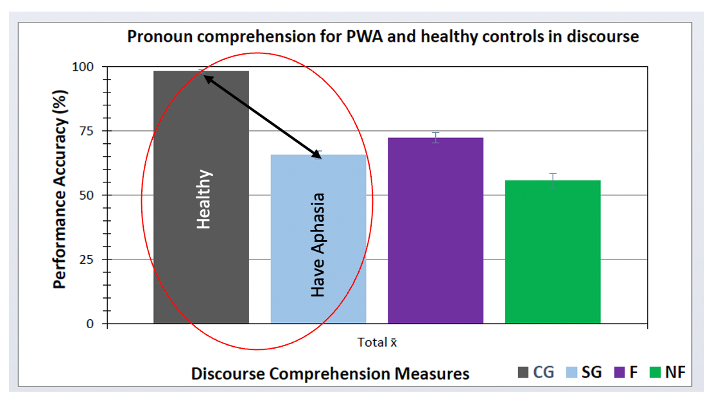

In one study2, the difficulty understanding pronouns in discourse is stark. Around one-third fewer of people with aphasia compared to healthy subjects could not understood pronouns in discourse.

When it comes to expression, there is a common resource for assessing aphasia that Speech and Language Therapists (or Speech-Language Pathologists) use called “The Cookie Theft picture”. (I rather enjoy how utterly stereotypical this. There have been attempts to update this picture but that’s a whole other blog).

Here’s an example of an agrammatic response3 to looking at this picture:

B.L.: Wife is dry dishes. Water down! Oh boy! Okay. Awright. Okay… Cookie is down ... fall, and girl, okay, girl ... boy ... um…

Examiner: What is the boy doing?

B.L.: Cookie is ... um ... catch

Examiner: Who is getting the cookies?

B.L.: Girl, girl!

Examiner: Who is about to fall down?

B.L.: Boy ... fall down!

Not a pronoun in sight.

When it comes to aphasia, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in pronoun processing.4 This means that treatment or support for the problem is per individual. There is no one way to approach the difficulty. Demands to use preferred pronouns or gender-neutral language thus make it more difficult for the person with aphasia to communicate.

Here are two examples of different types of aphasia.

Non-fluent:

Fluent:

Apraxia of speech / dysarthria / dysfluency

These are different diagnoses arising from different causes but all result in difficulties with speech and how clearly the person comes across to the listener.

A person with apraxia of speech has usually had a stroke or brain injury. It is a motor-programming disorder. They will pronounce words in different ways on each time of trying. And that’s if they can get the word out at all. They may pronounce the target word “window” as:

W w w w w…

Dindow

Wintow

Derwin

Wodow

Wind

Ow

Glafit

Nerwit

Etc.

Imagine insisting someone with apraxia of speech consistently pronounces neopronouns.

Here’s an example of apraxia of speech in an adult:

A person with dysarthria has a muscle weakness or reduced range of movement of the muscles for articulation or they just can’t get an accurate word sound out. There are lots of different types of dysarthria depending on the cause, which could be a stroke, brain injury or neuro-progressive disease or a developmental cause.

So dysarthria presents in lots of different ways and each individual with dysarthria may be clearer at one time of day or another or easier to hear in a quiet room on 1:1 than in a busy, noisy environment.

The ASHA website details how many different speech characteristics can be involved. Imagine expecting someone with Huntington’s Disease to achieve clarity of speech when differentiating “he” or “she” or using a neopronoun when their speech may be significantly impaired.

Here’s an example of speech in an adult woman with dysarthria:

You may understand this best as ‘stammering’ or ‘stuttering’. Some adults have had this since childhood, others acquire it after a stroke, brain injury, neuroprogressive disease or mental health condition.

Dysfluency comes with many outward and inward aspects.

And by the way, there are sex differences in stammering. It’s more common in males.

Quite how you would expect someone with any of these articulatory communication disabilities to consistently express any word is utterly unreasonable.

Here is an example of a young man whose speech is dysfluent:

Cognitive-Communication Disorder

A cognitive-communication disorder (CCD) can be the result of stroke, brain injury, neuroprogressive diseases, and mental health conditions. It can affect:

Attention (selective concentration)

Memory (recall of facts, procedures, and past & future events)

Perception (interpretation of sensory information)

Insight & judgment (understanding one’s own limitations & what they mean)

Organization (arranging ideas in a useful order)

Orientation (knowing where, when, & who you are, as well as why you’re there)

Language (words for communication)

Processing speed (quick thinking & understanding)

Problem-solving (finding solutions to obstacles)

Reasoning (logically thinking through situations)

Executive functioning (making a plan, acting it out, evaluating success, & adjusting)

Metacognition (thinking about how you think)

Are you really expecting someone who has CCD to use preferred pronouns or know what this sign means?

Here’s a man explaining some of the problems he had at work arising from cognitive problems after a brain injury:

and this is a good interview that summarises the problems:

One group of people who experience CCD are those with dementia. Language difficulties are recognised as a major problem for people with dementia5. There are many different types of dementia and each individual has specific cognitive-communication difficulties. However, it is well recognised that people with Alzheimer’s disease dementia experience:6

Impaired understanding of pronouns

Abnormal over-use of pronouns

Working memory impairment

And that it is best that conversation partners avoid pronouns in favour of “concrete, specific and simple words”.7

The ability to process pronouns, indeed any language elements, is diminished in all dementia types.

Alzheimer’s disease

Vascular dementia

Mixed dementia

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Frontotemporal dementia

Young-onset dementia

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD)

Alcohol-related dementia

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND)

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

Learning disabilities and dementia

Rare dementias

Again, is it reasonable to expect that someone with any of these difficulties could understand, process and/or use preferred pronouns or gender-neutral language consistently and effectively?

Here’s a video that shows how difficult it is for a man with Alzheimer’s Disease dementia to process sounds and language:

Psychosis language

Psychosis is the word used to describe conditions that affect the mind.

As the NIMH point out,

Psychosis may be a symptom of a mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. However, a person may experience psychosis and never be diagnosed with schizophrenia or any other mental disorder. There are other causes, such as sleep deprivation, general medical conditions, certain prescription medications, and the misuse of alcohol or other drugs, such as marijuana. A mental illness, such as schizophrenia, is typically diagnosed by excluding all of these other causes of psychosis.

Postnatal psychosis is a severe form of postnatal depression and women with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are more likely to experience it.

There are 3 main symptoms of psychosis:

hallucinations

delusions

disturbed, confused, and disrupted patterns of thought

And within the latter, signs include:

rapid and constant speech

disturbed speech – switching from one topic to another mid-sentence

a sudden loss in train of thought, resulting in an abrupt pause in conversation or activity

It can also be understood as 3 main types of disturbances:

disorganized speech - positive thought disorder

poverty of speech - negative thought disorder

flat affect

The use of nonwords or word approximations are often present in psychotic disorders.8 See here for a very comprehensive list of descriptions and examples of observed language production abnormalities in psychosis.

Disorganized speech can be made up of neologisms, “word salad” and tangentiality. This short video explains it really well:

Imagine you’re an adult with a mental illness that results in language abnormality or disability. How would you get on at University? As a patient in the NHS? As a victim or accused in the justice system? How could you possibly understand or use preferred pronouns, or gender-neutral language?

Hearing impairment and d/Deafness

As previously stated (above) for children, the same goes for adults. If an adult has hearing impairment and does not hear a word effectively, he may misunderstand its meaning or cannot also articulate that word clearly, especially if it is a neologism and even more so if it does not follow the phonotactic rules of English.

Hearing loss in older people and its link with cognitive decline is complex.9 Accurate diagnoses and appropriate support is essential to help people communicate effectively who have hearing impairment and/or cognitive problems.

As this NHS video about talking with d/Deaf patients states, even the best lip readers can only follow about 35% of what is being said:

And here is the Deafblind manual explained in a video:

Summary

As you’ve just read, communication disorders are many, varied and complex.

In significant numbers of adults, communication disability can initially be non-visible to a conversation partner, who does not know them (well). Only once you begin to enter into a conversation (or fail to) does it become apparent that the person has a problem.

If everyone in a workplace or school or University or ward or court-room is expected to follow a policy of ‘inclusive’ language that centres around gender but forgets about communication disability, then that is thoroughly unfair, unjust and in some circumstances, may even be against the law.

In PART FOUR, we explore the legal bit on discrimination.

See you in your inbox soon.

Goldberg E,B., Hillis, A.E. 2022. Sign language aphasia. Handb Clin Neurol.;185:297-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823384-9.00019-0

Devers, C., Howard, D., Webster, J. 2016. Pronoun Processing in People with Aphasia. In: 2016 International Aphasia Rehabilitation Conference, 14 December 2016- 16 December 2016, London, UK. https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/4217/

Avrutin, S. 2001. Linguistics and agrammatism. GLOT International, 5 (3), 111.

Martínez-Ferreiro, S., Ishkhanyan, B., Rosell-Clarí, V., Boye, K. 2019. Prepositions and pronouns in connected discourse of individuals with aphasia. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 33:6, 497-517, https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2018.1551935

Banovic S., Zunic, L.J., Sinanovic, O. 2018. Communication Difficulties as a Result of Dementia. Mater Sociomed. Oct;30(3):221-224. https://10.5455/msm.2018.30.221-224

Almor, A., Kempler, D., MacDonald, M. C., Andersen, E. S., & Tyler, L. K. 1999. Why Do Alzheimer Patients Have Difficulty with Pronouns? Working Memory, Semantics, and Reference in Comprehension and Production in Alzheimer's Disease. Brain and Language, 67(3), 202–227. https://doi.org/10.1006/BRLN.1999.2055

Rau, M. T. 1993. Coping with communication challenges in Alzheimer’s disease. San Diego, CA: Singular. pp77.

Hitczenko, K., Mittal, V.A., Goldrick, M. 2021. Understanding Language Abnormalities and Associated Clinical Markers in Psychosis: The Promise of Computational Methods, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 47, Issue 2, March, Pages 344–362, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa141

Uchida, Y., Sugiura, S., Nishita, Y., Saji, N., Sone, M., Ueda, H. 2019. Age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline — The potential mechanisms linking the two, Auris Nasus Larynx, Volume 46, Issue 1, Pages 1-9, ISSN 0385-8146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2018.08.010